Warning: this article contains spoilers for the video games BONEWORKS and Duck Season.

We live in a world in which people are becoming increasingly alienated from one another. Social media is driving people apart, the COVID-19 crisis encouraged people to stop seeing one another in real life, and at the same time virtual reality is gaining in popularity.

As someone who’s trying to regain a true sense of community in the real world, VR should be the last place I should be spending my time in. And yet the nerd in me keeps thinking that there are valuable experiences and lessons to be derived from this new storytelling medium.

BONEWORKS by studio Stress Level Zero was a great example of this, on the level that Metal Gear Solid 2 was in its time. Back in 2001, its director Hideo Kojima pushed the boundaries of video game storytelling to get you to question the nature of your relationship to video games and even to reality itself, using postmodern philosophy and clever storytelling twists to really make you reflect on why you’re even playing the game in the first place. You can see how much further a video game could push this further thanks to VR technology.

The best (and at the same time worst) aspects of VR

First, let’s talk about the experience of being in BONEWORKS itself which was initially very unpleasant for me. I’ve played a lot of VR games, and I rarely got motion sick from them, except a little at the very beginning, and yet the first hours in this game were a nightmare: intense nausea, sweating, dizziness, it was so bad I almost gave up on it altogether, but being kind of a masochist, I pushed through, and I’m glad I did.

A quick Google search will show you that motion sickness is very common with BONEWORKS, but the players (and the developers) can’t seem to agree on what is the exact cause of it. Some will say it’s the locomotion, some will say it’s because you have a full visible body instead of the usual floating hands that you find in most VR games. My personal theory is that the game feels just a bit too real. One of the avowed goals of the developers was to transpose as many real life mechanics to the world of BONEWORKS: you can basically interact with the whole environment, from smashing bottles, to handling a rifle, to stacking up piles of crates to solve one of the games’ puzzles.

They did this well, a bit too well, to the point that it messes up with your perception. Nausea will become especially intense as you’re getting tangled up inside the game but your real body cannot feel anything. Where other VR games will simplify the interactions to some extent to prioritise accessibility and expediency, BONEWORKS tries to keep them as complex and realistic as possible. The downside is that the controls can feel a bit clunky and clumsy at times, as your in-game body gets stuck as a real body would.

Because of that, it took me a few hours of gameplay before I started actually enjoying myself. It also didn’t take me long to get gripped by the story, or at least the little I could glean from it. The game deliberately maintains an aura of mystery and relies on the players (yes, plural) to figure out what’s going on. Sadly, I couldn’t make out much of the meaning and ramifications of its complex and multilayered story on my own. So while the game still offered an overall enjoyable experience, most of the fun was to be had watching video analysis of the game’s story.

BONEWORKS does a good job pulling you into its universe which is paradoxically fascinating and creepy at the same time, its atmosphere being helped by the realistic mechanics and the immersion offered by VR. Despite the frustration caused by the motion sickness and the sometimes tedious controls, I wanted to know more.

What happens if you die in the Metaverse?

It’s kind of surprising to see a game like BONEWORKS gather so much enthusiasm, it being from a niche genre on the niche platform that is VR. After all, the makers of the game themselves advertise that the game is “for advanced VR players only”. I believe the interest and the cult following the game has garnered has a lot to do with the zeitgeist we find ourselves in. The game presents you with a world in which it is possible to directly upload your consciousness into a virtual world via a virtual reality headset.

Does that ring a bell? This is more or less what Facebook (excuse me, Meta) is developing at this very moment with its Metaverse. Although it would still be a world you would see through goggles, Mark Zuckerberg certainly wouldn’t mind immersing you as much as possible. As long as the technology will allow it, he certainly won’t see anything wrong with it. And of course, BONEWORKS wouldn’t have a science-fiction story worth its salt if it didn’t try to show you how this project could go horribly wrong.

The world of BONEWORKS is extremely complex so I will try to simplify it as much as possible for the purpose of this article. The game is set in an alternate reality to ours, the technological advancements mirror more or less the ones you can find in our timeline except for one important difference, some kind of quantum leap was achieved in the realm of VR technology.

When you put on the headset, your consciousness gets transported to another reality which not only feels real to you, but is also actually real. The scientists and developers find a way to harness the environment and to build a safe space for humans (or human consciousnesses) inside of it. And the building is not done in an abstract manner, actual AI units appropriately called the NullMen are needed to physically build the world contained in that space. Also, each person that enters the virtual environment needs a body to be able to navigate it safely.

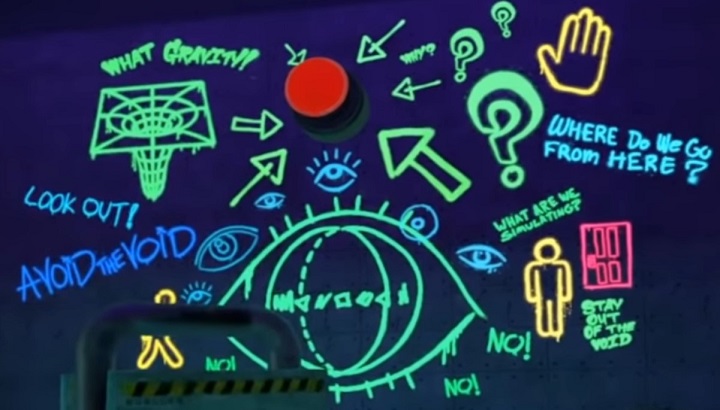

That viable space is called MythOS and is basically the game’s equivalent to to the Metaverse. The space outside of it is chaotic and will harm your character if he comes into contact with it. It is also appropriately called “The Void”.

You play as Arthur Ford, the security director for one of the companies which is extracting an habitable environment from The Void. Understandably, a number of security protocols have been put in place so that the VR environment called MythOS remain safe for its users. For example, if you die in it, you’ll be resurrected or respawned just like in any video game.

The question that arises is: what happens if you manage to die outside of the safe space provided by MythOS? The main character of the game thinks it would allow him to achieve immortality, by permanently freeing him of the constraints of his virtual body and his real-life body altogether.

Real Gnosticism has never been tried

Escaping this dirty body and plane of existence was the dream of the Gnostics of yore, and it is the dream of contemporary Gnostics like Yuval Noah Harari. They think that technology will provide us a way to break away from the shackles and limitations of our bodies, which they see as a prison shell limiting our potential. Arthur Ford thinks this is a great idea and he actually achieves his goal. Harari and his followers would most likely see this as a happy ending. In the final scene, you see your real life character getting a bullet through the head while you do not lose consciousness in the Void. If you don’t pay too much attention to the story of the game or the meaning of the signs which are given to you along the way, you could easily see the triumph of the main character as something positive.

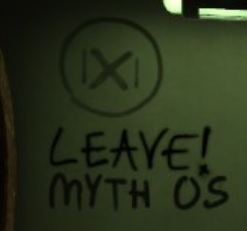

Your progression through MythOS will be impeded by multiple obstacles, whether from the environment itself or a kind of police which sees you as a foreign entity to be eliminated. In other words, a virus. You will also see various messy messages on the walls. The origin of the messages is unclear. One of them seems to be from other versions of Arthur Ford himself who are aware that other iterations of themselves will be coming down the same path. Some messages encourage him to continue and provide helpful clues, others beg him not to go any further. Other messages appear insane, full of despair or evil. And finally, there are benevolent and helpful messages which are genuinely trying to help Arthur, signed by a mysterious character named |X|.

Along the way, you will also encounter many versions of yourself. The “best” versions are Fords who apparently have spent so much time trapped in MythOS that they have forgotten who they were. They are either mute or repeat the same sentences over and over again, but they’re not threatening and even helpful at times. The “worst” versions are zombies that will try to attack you on sight.

The meaning of these messages or iterations of yourself that are encountered is entirely up to the player. Some people (like myself) will see the malevolent messages and zombie versions of the character as obviously meaning that his project is a terrible idea and that he (and you, the player) should get the hell out of there while he still can. And others could interpret the messages and other selves as a trick from the MythOS system, and if they’re willing to take that leap, they could just discard the Fords who have failed and ended up as zombies or demented as a small price to pay to achieve immortality. It reminded me of the movie The Prestige in which (spoiler alert) Hugh Jackman’s character duplicates himself for a magic trick, knowing that his clone would drown in a water tank.

From a purely materialistic standpoint, there wouldn’t seem to be anything wrong with having your consciousness live eternally in a Matrix-like environment. For many it would seem to be a reasonable alternative to living your earthly life until your fleshly body expires and you’re condemned to eternal nothingness. The world of BONEWORKS certainly primes you to seeing its world through that materialistic lens.

The different zones of the game generally have that cold, grey futuristic look you find in dystopic science-fiction stories. The whole setup looks like this bitter pill to swallow so that a better plane of existence can be reached. At best you can succeed at becoming this limitless god, and at worst, you die. Because that’s the worst that could happen to a materialist. There is no third option.

Opening portals to the demonic

But what if there was an other way of seeing it? What if on the other side of that Gnostic trick, there was a inescapable hell awaiting for you, and an eternity of suffering? The game for all its scientistic appearances actually gives you hints that it could be the case. The warning messages on the walls are obviously one of them, if you don’t dismiss them as a trick of the system. But there are others, if you’re attentive during your progression, you might notice some kind of ethereal human shapes that disappear if you try to get closer to them. It is hard to get a good look at them, until your reach the final scene of the game where you see Arthur Ford’s physical body being killed in the real world. Several of these entities appear in the room, and you can see them contort themselves, as if they were in excruciating pain. The BONEWORKS community has speculated that these entities are the Fords that have succeeded desperately trying to warn you and the other Fords not to make the same mistake.

What if the alternate reality which you access through the ultra-immersive VR technology isn’t simply another set of dead matter to rearrange to our liking? After all, this is still how most people perceive the world in the West.

What if on that other plane of existence, there were entities with a will of their own? Thankfully, this isn’t just me speculating, as BONEWORKS isn’t the only game set in the universe created by developer Stress Level Zero. In its 2017 VR game Duck Season, you discover that what I’ve just described is actually the case.

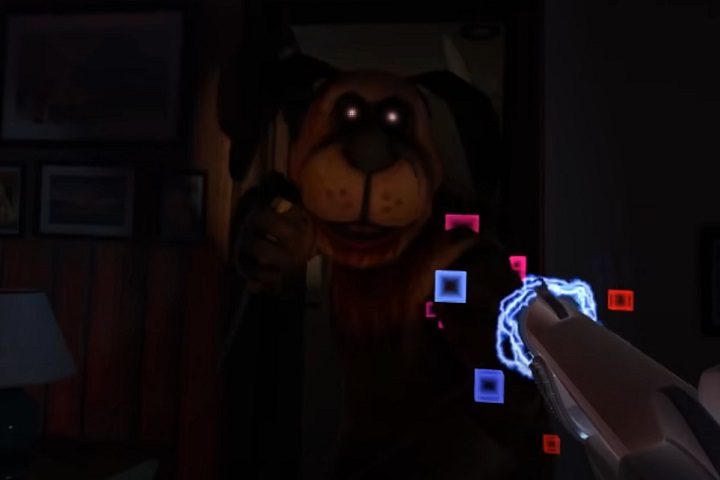

To summarise the plot, you’re an 80’s kid who gets a VR video game called Duck Season for his birthday. It is that world’s equivalent of the game Duck Hunt which came out on the NES console in 1984. The difference here is that it uses that ultra-immersive technology, so the kid is not just aiming a gun at the TV, he actually enters the world, which like MythOS was built by creating a viable contained space in The Void. What starts out as a fun evening playing a video game quickly turns into a horror story when one of the characters of the game, a person in a dog costume, crosses into the kid’s reality and brutally murders his parents.

The writers of Stress Level Zero have call creatures like this person in a dog costume cryptids. In our world, cryptids refer to those creatures often seen in the wild, whose existence cannot be proven scientifically. Famous examples include Bigfoot, Yeti and the Loch Ness Monster. The dog isn’t the only cryptid in Duck Season, there is also a monkey puppet and a cat clock that both have evil intent. You find them in a secret room in the game and accidentally send them to another reality, each of them being another Stress Level Zero game. So we see this interconnectedness between worlds, with entities that can move from one plane of reality to another, but only through the misguided help of a human who would have been better off never crossing paths with them.

Human revolution

Once the above is taken into account, it is clear that Arthur Ford is doing more than something like reaching what futurists like Harari see as the next step of human evolution. People on the more secular or progressive side are really banking on the idea that pursuing such endeavour has no moral implications. Notions of good and evil are beside the point and dismissed as ancient superstitions designed to keep humans from achieving their true potential through a merging with technology. Any objection and warnings that they get from people on the more religious side are to be regarded as suspect, just another trick used to keep humans down, only delaying a revolution that they see as inevitable.

Speaking of revolution, the game also provides a near perfect image (and experience) of how selfish and self-destructive Ford’s quest is by having you reach a hidden part of MythOS that set in a medieval kingdom called Fantasy Land. In it, the people are all clones of Arthur Ford that forgot who they were and are ruled by a king who is also Ford. In order to progress to the Void, where you’ll finally be able to achieve “immortality”, you have to kill the king of the Fords with your bare hands. The fight is set up in a hybrid castle-church in which you see stained-glass windows depicting Ford as a prophet, as a warrior and even as the messiah of Fantasy Land.

This is where VR makes the experience particularly intense and visceral. Remember that the game is extremely realistic. So here you are, basically trying to pin down yourself and smashing any object you can get your hands onto his face, you see him get bruised and bleed as he is laughing in your face, and the crowd of your other selves is watching. If participating in that scene doesn’t make feel a bit sick to your stomach, you might be a psychopath. Once you’ve managed to beat him to death, you can pick up the crown and put it on your head. When you put the crown on your head, you will also hear a ridiculous videogame-ish “ta da!” sound.

The imagery is reminiscent of what rapper Lil Nas X showed in his video clip Montero, where he appears in a world full of clones of himself and ends up killing the devil to steal his thorns and uses them as a crown. In this article, symbolic thinker Jonathan Pageau shows how archetypal this move is, from Adam and Eve taking the fruit of the knowledge of good and evil for themselves, to Napoleon crowning himself, to Lil Nas X reveling in the same ultimate act of self-glorification. Ford is another example of the same pattern of revolution against the way things are, against what you have been given in this life.

Like in all revolutions, bloodshed inevitably ensues as Ford is progressing towards his goal of (what he sees as) immortality. The suffering that is caused along the way doesn’t seem to bother him, just like Hugh Jackman’s character isn’t bothered by the clones of himself drowning so that he can achieve his goal of becoming the best magician. To them they appear as a necessary sacrifice.

All along the game is telling you not to go any further with its eerie writings on the wall, some seeming to speak directly to you the player, like Metal Gear Solid 2 was doing back in 2001. The game wants you to regard yourself as an accomplice of what is happening to Arthur Ford.

Conclusion

Reaching the finale, you won’t feel any sense of triumph. It was like the diametrical opposite of watching Aragorn being crowned by Gandalf (and not by himself) at the end of Return of the King. There was no joy to be felt, only unease and confusion, at least for me. In that sense, BONEWORKS is a great cautionary tale that is simultaneously happening in the game itself and to you on a meta level.

Do not try to escape reality through the use of (VR) technology, while using that same technology to escape reality, because you might just come in contact with demons that will lead you down a dark path, inflicting infinite suffering to seemingly infinite versions of yourself and either ending up a lonely king or trapped in-between worlds condemned to eternal suffering. Ford, through you the player, condemns himself to hell and fails at stopping the process for his other selves. From hell, he’s urging them to repent and abandon the pursuit that will lead his other selves to the same place. In vain.

It is not all dark though, as there are still the messages on the wall signed by this mysterious |X| character that seem to genuinely want the good of Arthur Ford and this at every level of the progression to the very end of the game. If you ask me what this character represents or points to, all I will do is refer you to the banner of this website.